A little break

It was Christmas, and I had a birthday, and then we had a new year’s holiday and I had a couple of days out of the office. I still don’t have any superpowers, but I did get to spend time binge watching The Muppet Show with my kids, so I am counting Parenting as another one of my everyday superpowers that I continue to manifest.

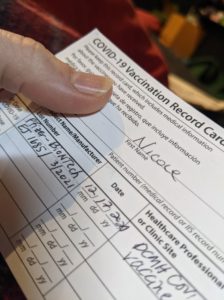

Without intending to, that was a whole two weeks where I didn’t update and – as I mentioned – I received my second vaccine yesterday. I will strive to be a little more consistent in the next week or two.

We’ve seen some news reports lately about severe reactions to coronavirus vaccines. In addition to the reporting system we have always used for severe vaccine reactions, the CDC has rolled out a smartphone-based monitoring system called V-Safe specifically for tracking the health of people who’ve received the coronavirus vaccine.

A recent review of the adverse event reports for a 10 day period in December showed 1.9 million doses delivered (exciting!) and a little under 4,400 reports of “adverse events” (things we’re concerned about). About 175 of those events were of concern as possibly being severe allergic reactions, and about 21 of those events appeared to be true anaphylaxis (a life-threatening allergic reaction that overwhelms your body). That works out to about 11 cases of anaphylaxis per million doses – definitely more than the flu shot (1.35 per million), which is why our current practice is to give the vaccine in a clinic that is equipped to identify and treat anaphylaxis.

At regular intervals, V-safe texts me a little survey to find out how I’m feeling, if I have developed any new concerns, or if I have gotten pregnant in the interim (nope). It also sent me a reminder to get my second dose. If you’re getting vaccinated (or have been already) and are not signed up, I’d encourage you to get registered!

I will tell you the same thing I told V-safe: I feel good, but my arm hurt a little earlier today. It started about 18 hours out but at this point in the evening I really am not having any symptoms at all. I will also tell you that I have colleagues who have complained of fever, headache, and generalized yuckiness as far as 2 days out from their second dose, so I’ll continue to watch.

(To give another perspective on risk — although you can’t make a direct comparison — today’s numbers in Indiana show 558,560 individual Hoosiers have tested positive for coronavirus and 8,595 Hoosiers have died of COVID. That is about 15,000 deaths per million cases.)

Science continues to move at a rapid rate, and recommendations continue to be updated as we are looking at balancing availability of vaccines with people who need to receive it, as well as looking at the reports of people who have received the vaccine. Since I last posted, the recommendations regarding people who have already had coronavirus have evolved. CDC’s current recommendation is that if you have had coronavirus within the last 90 days you may choose to wait to receive your vaccine. If you received monoclonal antibodies or convalescent plasma (you should know who you are but if your sick days are hazy your doctor will know) then you definitely should wait 90 days (and discuss with your doctor the best timing for being vaccinated).

We are seeing at least anecdotally some degree of more robust vaccine reactions in people who have already had COVID (in plain English: If you already had coronavirus, your body is already somewhat primed to recognize and respond to the vaccine, and so it may be more likely that you are going to have a day or two where you feel yucky). It makes sense, if you already have protective antibodies, that you can choose to wait a few months — your immunity is not likely to fade that fast.

However, if you received monoclonal antibodies (that’s an outpatient infusion that ends in MAB), what we are giving you in that infusion is literally a cocktail of antibodies. These are designed to augment your body’s response, targeting and inactivating the virus and limiting its ability to continue to spread through your body. There’s a similar idea behind convalescent plasma (that’s an inpatient infusion given in some centers to specific patients), except instead of laboratory-grown antibodies, the plasma is extracted from people who have already recovered from COVID-19.

Bodies are not so smart sometimes: your body assumes those antibodies are home-grown – and so, when you receive your vaccine, you may not make quite as many antibodies of your own if you have a whole bunch of artificial ones floating around already. That’s why we recommend you wait.

I had a little list of questions and thoughts to cover before I took an accidental vacation. I suspect they’re still relevant.

If I have asthma or epilepsy, should I take any precautions regarding this vaccine?

As far as we know, the coronavirus vaccine does not show any increased risks for people who have asthma or epilepsy. However, it’s important to remember that these diseases, like many diseases, have a wide spectrum of severity. We know that some people who have epilepsy show an increased risk of seizures if they have a fever, are under physical or emotional stress, or when they are even mildly ill, and so if you are one of those people you should definitely talk to your doctor about their recommendations. Similarly, if your asthma tends to flare up when you are under stress or not feeling well, you should check in with your doctor.

What if you were tested for antibodies after your COVID-19 illness and were negative?

Short answer: OK to be vaccinated, although you could certainly consider waiting for 90 days after your recovery.

Long answer:

There’s more to immunity than antibodies. Your immune system also has “memory cells” whose job it is to be ready to recognize a specific antigen (remember, an antigen is anything your immune system recognizes as “not me”) and produce antibodies rapidly. We don’t completely understand how B and T memory cells are formed and do their jobs, and we don’t have easy tests to measure the efficacy of those cells, but we know that they can last for decades. That’s where the real staying power of vaccines comes in: they activate the memory cells of the body. In fact, there’s some evidence that your memory T cells are activated proportionately to your vaccine response, so those of you who get a hefty reaction to the coronavirus vaccine can take comfort in knowing you’re building immune memory for decades to come.

Should COVID long-haulers have any special considerations?

At this point in the pandemic, we recognize what’s called “long haul COVID” as symptoms that develop during or after COVID-19 infection, continue for ≥12 weeks, and cannot be explained by an alternate diagnosis.

Let’s break that down, shall we? It is at this point considered the normal clinical course of COVID-19 to have symptoms for up to 3 months following your diagnosis. Studies suggest at least 1 in 10 (and up to ¾ or more) of symptomatic people will have some lingering symptoms for 6 weeks to 3 months after COVID, and while fatigue is the most common complaint, we are also seeing significant numbers of patients experiencing shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, memory problems, concentration issues, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. My clinical experience — what I’m hearing and seeing in my own patients — tells me this is right on the money. COVID is no joke.

Long haul COVID patients are experiencing some portion of these symptoms for more than 3 months. As doctors, we are in the business of helping people, but we have very few effective treatments for these symptoms, and so treatment mostly consists of trying to find something that’s measurably wrong (lung damage, heart muscle damage, blood clots, things like that) so we can target therapy.

The good news is that none of this seems to impact your ability to get the coronavirus vaccine. Your immune system may have been complicit in the processes that got you there (we don’t completely understand why people are affected so differently, but immune system responses likely play a part), but it’s unlikely to turn traitor with regard to the vaccine.

Now I think I’m caught up with questions.