Everything mutates.

We went to the Children’s Museum this weekend. We wore our masks and admission was limited to 25% of museum capacity (and it was not full), and we stayed in our pod. We saw an uncomfortably large number of noses poking out in some areas of the space and a comfortably cheerful number of museum staff reminding us not to let our noses poke out.

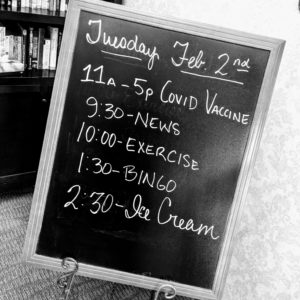

Being fully vaccinated gave me a strange sense of comfort, even though I wore my mask the whole time and sanitized my hands every twelve steps. It was interesting to watch my spouse – who has not spent a lot of time outside the home since last April – try to walk the balance between extroversion and caution. We are going to have a lot to re-learn as a society, I think.

A dear friend of mine who doesn’t always agree with me asked an interesting question, and it dovetails with another question that I’m starting to hear in medical conversations as well, so today’s diary ambitiously attempts to cover both of them:

What about the virus mutations? Will the vaccine protect me from them?

How does this all end? We can’t go on forever the way we are, so what happens in the long term?

Short answer: We don’t know (yet), but we have some educated guesses, and most of them revolve around our experience with other respiratory viruses (coronaviruses, influenza viruses, and the like).

Long answer: Science (primarily virology and epidemiology) ahead!

I briefly covered viral structure in general in another post, but it’s going to be important to the conversation ahead, so let’s go ahead and talk a bit more about that as it relates to SARS-CoV-2. This is a coronavirus – part of the coronaviridiae family, which are a relatively small group of enveloped RNA viruses with pleomorphic properties, bearing club-shaped surface proteins and measuring about 100nm in size on average.

In other words, humans have defined coronaviruses as a specific set of little bags of proteins covered in knobs. It’s the knobs that are going to be the focus of our discussion, and specifically the S (spike) protein in the knobs, which is the part that connects to your cells and allows a coronavirus to infect them.

When that happens, the S protein plugs into an ACE2 receptor on your cells, inserting itself like a clumsy sort of key into a loosely-constructed lock. We’re not going to go into the biochemistry of all of this (I hated biochemistry, I’ll be honest), but this connection allows the envelope of the virus to fuse with the cell it’s infecting (imagine a couple of soap bubbles merging, only one of them is full of instructions for making a zillion more bubbles). The virus inserts its instructions for assembly into the “host” cell’s manufacturing sites and then its work is done. The host cell makes a bunch more viruses, which go out and infect other cells, and so on.

There are seven different strains of coronaviridiae that are known to infect humans. We discovered SARS in 2003, MERS in 2012, and COVID-19 in 2019, which makes them all still newcomers on the global disease playing field, and all three remain deadly at this point. Those are the big players in the coronavirus game, if you will, with COVID-19 actually having the lowest kill rate of the three.

The other four strains are the coronaviruses mentioned on bottles of Lysol and cleaning wipes since well before 2019; these are the sort of low-grade obnoxious respiratory virus that contributes to the group of symptoms known as the “common cold”. Common cold coronaviridiae are the ideal future of SARS-CoV-2: the virus eventually becomes nothing more than a nuisance to the vast majority of humans. Unfortunately, it may take a while – especially for a slowly-mutating virus like this one – to get there.

Which brings me to the topic of vaccines, mutations, protection, and adaptation.

Viruses mutate. When a zillion copies of a virus are being produced, there will inevitably be some errors introduced into the RNA as it’s being copied. Sometimes, those errors in copying produce changes in the virus that help it in some way. Changing a single amino acid – for example, let’s switch aspartate to glycine at position number 614 – means the spike protein connects more easily to the ACE2 receptor, which means the virus can infect cells more easily, which makes it easier for it to spread from person to person. Now let’s call it the D614G strain and sound like a virologist, and then publish a paper about the new mutation we’ve found.

Because science is moving so FAST these days, we may choose to publish a pre-print version of the paper to the Internet, in order to get our conclusions out into the open so others can use them. That pre-print version has not, however, been peer-reviewed (remember peer review? It’s where other scientists look at your data and your conclusions to double-check, in case you missed something) and so it’s important for other people to remember that when they’re reading your conclusions.

A lot of the information about the recent viral mutations: B.1.1.7 (UK variant), B.1.351 (South African variant), P.1 (Brazilian variant) and G614 (oh hey you know that one now!) is still in pre-print or pre-published data. That means that I may be able to get my hands on the information (thanks, IU School of Medicine) but I am still waiting for people who are specialists in the field to look over these papers for things I may not know I should be concerned about before I trust their data.

So here’s what we do know:

Increased transmissibility (person to person spread) does not necessarily mean that a variant is more deadly. The G614 mutations (and there are several) have not seen an increase in hospitalization rates despite becoming more dominant than the original strains. We don’t have enough data to be sure about the B.1.1.7 variant yet; it may be a bit more serious than the original, but only a bit.

What increased transmissibility does do is increase the risk that at-risk persons are going to become infected, just because it’s easier for this variant to spread from person to person. It’s a much friendlier and more outgoing version of the virus – it’s likely to be on the Virus Cheer Team and the Virus Student Council. However, both the G614 and B.1.1.7 variants appear to be effectively prevented by vaccines at this point. They may be fun and outgoing, but they still look enough like the Wanted poster that nobody is going to be fooled for long.

Other mutations in the spike protein give us more cause for concern. These are the mutations that change the way it looks to your antibodies — the viral equivalent of a dye job and a pair of shades in the dark. B.1.351 is one of these mutations – it may have increased transmissibility, since it is now the dominant strain in South Africa – but it probably is not as attractive to neutralizing antibodies in a test tube.

All of this data, as of right now, is in pre-print status. That means it’s still being looked at. It also means that this is New Science! A lot of it is happening in the lab at this point, so that’s another important factor to consider.

Bodies are super cool and extremely adaptable, and the things that happen inside your body are the result of complex interactions between all of your cells and systems, so the things that happen in a test tube (in vitro for you language nerds) may not happen the same way (or at all) in your body (in vivo). We’ve seen this with the initial antibody studies on COVID-19: early studies showed a rapid drop-off of antibodies in just a few months; the reality seems to be that people who have had COVID-19 retain their protection pretty well for much longer.

So what does all that mean for my ability to go watch a movie or safely reschedule my Disney trip sometime in 2021?

It means that if you are at high risk of dying from COVID-19 or of having long term complications of the disease, you absolutely should be having a conversation with your doctor about being vaccinated, because this virus is unlikely to go away any time soon. That protects you from symptomatic infection, which is important! It reduces your risk of hospitalization and death.

It means that if you are not at high risk of dying from COVID-19 you should strongly consider being vaccinated when you are eligible. I understand that you may be waiting for more data, and it’s happening all around us! You are still at risk of long-term complications from a coronavirus infection, and that is no laughing matter.

It means that we will — at some point — have to adjust the vaccines we have as the virus mutates. We know how to do this; we do it every year with the influenza vaccine as influenza strains mutate and fight for dominance. The rest of the vaccine will remain unchanged, so we will not have to go through new trials, but when that happens, vaccinated folks will probably need to get a booster shot.

It means that going forward, when you are sick, you should probably wear a mask (correctly, according to the best science that is available at that time) if you have to go out in public. If you are at high risk of getting sick and need to go out in public (because we do not live in a perfect world of protection) then maybe you will always want to wear a mask.

It means that each of us is going to have to engage in a personal calculus of risk and reward for each activity that we participate in. If you see someone wearing a mask – now and until we come up with something better – you should assume that they are doing the best they can to protect themselves and the people around them, and you should respect that as a fellow human being.

And until we have a whole lot of people vaccinated (I don’t know how many! That number is one that I don’t have data on yet), you should plan to wear your mask in public even if you feel well, to keep a respectful distance from people who are not in your pod, and to avoid crowding together in poorly ventilated spaces.

Don’t be afraid. We know so much more than we did a year ago, and we are learning more every day.

But be thoughtful. Be kind. Be a human in a world full of other humans, all of whom are complicated and messy and full of conflicting needs and desires. Plan your activities according to whether or not they can be performed in a way that keeps you and the people around you safe.

And remember that as we learn more – innovate more – understand more – we get better and better at making ‘safe’ look like ‘the old normal’ again.