Trust is a hard thing to measure

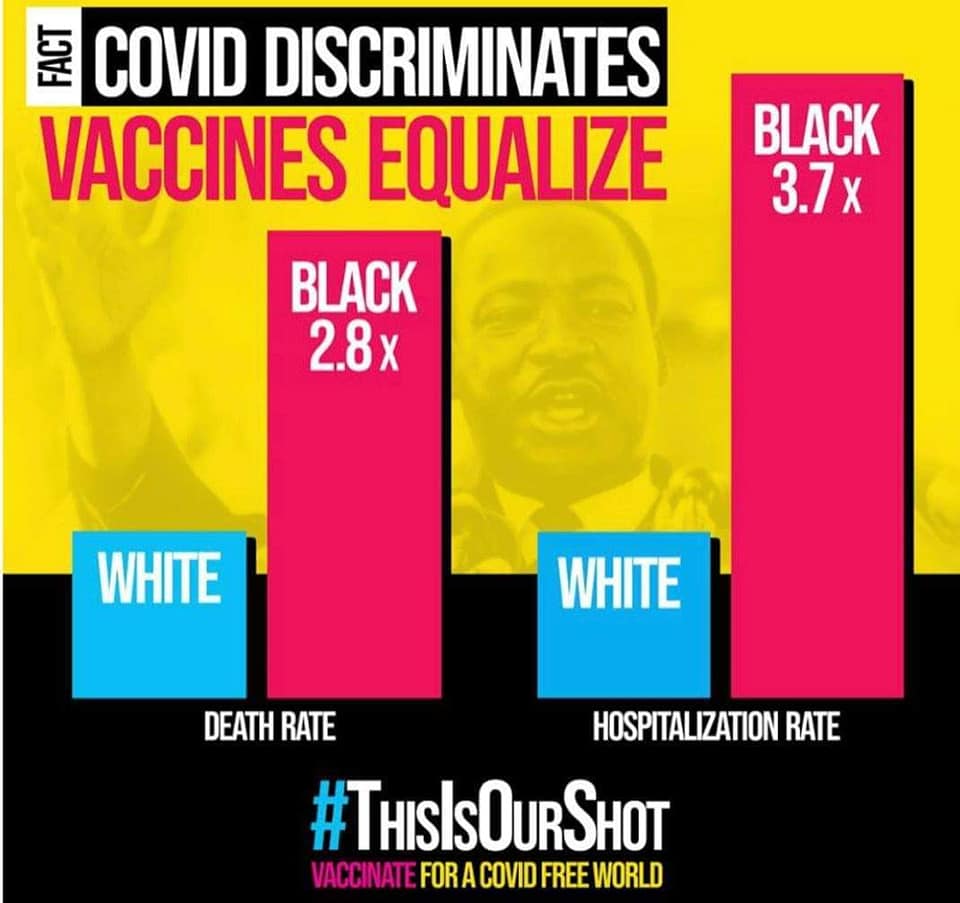

Today’s diary picture is the first one that is not from my own personal camera; I am sharing it from the #thisisourshot community because this graphic is relevant to the day and the topic at hand.

I sort of miss my daily “how are you doing?” texts from the CDC (I’m fine, V-safe, thanks for asking), but I’ve graduated to weekly check ins at this point. One of my nursing homes has had their first round of vaccinations rolled out, and tomorrow I’ll be at the second for an update. All of my frail elderly folks are doing great following dose #1, as are the not-so-frail and not-so-elderly folks who are residing there.

The Norwegian health authorities have a simply lovely website, and I stopped in there today to see what the latest word was (they even provide it in English for those of us who don’t speak Norwegian!). And the latest word is this: For the vast majority of elderly people living with frailty, any side effects of the vaccine will be outweighed by a reduced risk of a severe COVID-19 disease course.

However, for people with severe frailty and those with a very short life expectancy, even relatively mild vaccine side effects can have serious consequences. Any benefits of taking the vaccine may be small. For these patients, their doctor should make a careful overall assessment and, in consultation with the patient and their relatives, decide whether the patient should be advised to take the vaccine.

There’s a lot happening in the vaccine world right now! I want to talk about a whole lot of things! But today is Martin Luther King day, and while I was reading the Johnson and Johnson phase 1-2a results paper in the New England Journal of Medicine the other day for my pre-diary research (remember that diary? We have another vaccine coming!), something caught my eye.

That something was this sentence: “The demographic characteristics of the participants in our trial confirm the lack of representation of minority groups.” In other words: this trial’s participants overwhelmingly identified as White.

Why does that matter?

It matters because communities of color have been disproportionately affected in this country by this pandemic. The CDC’s data on race and ethnicity in COVID-19 cases shows that Black patients who get COVID-19 are 3.7 times as likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times as likely to die as are White patients. Hispanic and Latinx patients are 4.1 times as likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times as likely to die. American Indian/Alaskan Natives are 4 times as likely to be hospitalized and 2.6 times as likely to die. In short, these are numbers that can help us identify the groups of people who are at increased risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19.

It matters because when Pew Research surveyed Americans about their attitudes toward a coronavirus vaccine in late November of 2020, 61% of White and 63% of Hispanic respondents said they would “probably” or “definitely” get a vaccine if it were available at that moment, but only 42% of Black respondents said they would. Those are all numbers that need to be substantially higher, but when a group of people who are at increased risk of hospitalization and death reports that only about 40% of them are willing to take a potentially lifesaving vaccine (Pfizer released their Phase 3 trial data on November 18th, the day this survey opened), then we should – as scientists – ask why.

This is a diary about race and medicine. It may be uncomfortable to read. It is uncomfortable for me to write. I have taken more deep breaths in the last two paragraphs than in all my previous diary entries combined, and I haven’t even gotten to the story I want to tell today.

This is a diary about how – when the Indiana State Department of Health and the Fairbanks School of Public Health began a landmark study of population-wide coronavirus prevalence in Indiana – they had to make a special effort to collect enough data from minority communities to satisfy the statisticians (this whole study is an amazing demonstration of what public health research looks like, by the way).

It is a diary about why the National Medical Association (did you know about the National Medical Association? It was founded in 1895 after the American Medical Association refused to admit Black physicians as members) felt the need to convene a task force composed of So Many Specialists to meet with Pfizer and Moderna and independently review the data from both trials specifically with regard to the enrollment of Black participants.

For the record, the NMA task force concluded that “Both the percentage and number of Black people enrolled are sufficient to have confidence in health outcomes of the clinical trials.” and re-emphasized the >94% efficacy of the vaccines and the safety profile across age, gender, race, ethnicity and for adults over 65 years of age. That endorsement is important.

It is a diary about a 2002 study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine (put on your statistics hat: this study had a P of <0.01, meaning the results are less than 1% likely to be a random fluke of data) that found 41% of Black respondents did not trust that their physicians would fully explain research participation, compared to 23% of White respondents. Same study: 45% of Black respondents believed their physicians exposed them to unnecessary risks compared to 34% of White respondents.

This is a diary about trust.

It is a diary about a legacy of injustice that has come to be symbolized in the medical community by the word Tuskegee. And that is the story I want to tell today — not because I want to shame my colleagues, or point fingers, or cast blame — but because there is a reason many Black patients do not trust their physicians, or government-sponsored vaccine programs, or public health authorities. And as a medical profession, we are going to have to get pretty comfortable with being uncomfortable if we truly want to help our patients in the best way we can.

So stay with me for a little bit. I’m going to keep this strictly to the facts.

The Tuskegee experiment (full name: “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”) is not – by any means – the sole driver of Black patients’ mistrust in the medical institution. It is, however, a powerful example of the real events that inspired that mistrust. And it was carried out at the Tuskegee Institute in Macon County, Alabama, by the United States Public Health Service.

A word about syphilis, first: this is largely a sexually transmitted disease, but when left untreated can cause liver and kidney damage, dementia, blood vessel and heart damage, severe pain and death. It can be spread from an infected mother to an infant before birth and has permanent effects on growth and development. It is difficult to eradicate and can lie dormant for years. Today, syphilis can be effectively treated with long courses of penicillin, but in 1932, there were no effective treatments (arsenic and other toxic heavy metals were favorites for treatment). It represented a significant public health concern.

Fact: In 1932 the Tuskegee Institute partnered with the US Public Health Service to conduct a study on the “natural history of syphilis”. The study was intended to observe and record the ways that syphilis manifested itself in Black Americans. It was supposed to last 6 months.

Fact: 600 Black men – most of them poor sharecroppers, most of them illiterate – were enrolled in the Tuskegee study in 1932. They were promised free medical care, rides to and from their clinic visits, free meals on exam days, and burial insurance. For a sharecropper in 1932, this was quite a lot! The researchers told the men that they were being treated for “bad blood”, which was a catch-all term used for a variety of ailments at the time. About 400 of these men had syphilis, and about 200 of them did not. The precise numbers vary from report to report.

Remember where I said the study began in 1932 and was supposed to last 6 months?

Fact: In 1947, penicillin became widely known as the drug of choice for treatment of syphilis. None of the enrollees in the Tuskegee study were offered treatment with penicillin. Researchers continued to observe their subjects. A draft report from 1949 recounts the deaths of 140 men in the study in the first 16 years.

Fact: In 1968, a report from the ongoing study notes that 373 participants were known to have died (there’s no breakdown of cause), and only 89 participants showed up for their yearly medical examination. Of those, 53 were men who had syphilis. The report notes that only 4 of these patients remained completely untreated; 13 had been treated with penicillin (by 1968 a well-established standard treatment) and the rest with arsenic and heavy metals. The next year, an ad hoc committee met and decided that — despite moral and ethical concerns raised by committee members — the study should continue until all the participants had died.

Fact: The Tuskegee study ended in 1972 when the Associated Press broke the story of a forty-year experiment in non-treatment of syphilis. Public opinion led to Congressional hearings, changes in the rules around study design and consent, and a $10 million settlement for survivors and their families out of court.

Are you uncomfortable? Because I am.

It’s easy to say that an experiment like the Tuskegee study could never happen today – but 1972 was not so very long ago, and this is just one entry in the long history of the interactions between the medical community and communities of color in the United States. There are a lot more stories to tell.

This is a diary about rebuilding trust.

It’s a diary about becoming comfortable with being uncomfortable.

It’s a diary about getting vaccines into the arms of the people who are most at risk.

It’s a diary about a dream.

- References for today:

Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine Mitigating ethnic disparities in covid-19 and beyondImmunizations and African Americans – The Office of Minority Health

How to overcome COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black patients

NMA COVID-19 Task Force on Vaccines and Therapeutics – National Medical Association

COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity

COVID-19 Random Sample Study: COVID-19

Report on Tuskegee Syphilis Study