Ordinary Superpowers

It is the winter solstice today; the shortest day and longest night in this hemisphere. The days will slowly lengthen toward the dawn. Still no new superpowers. I’m going to have to stick with the ordinary superpowers that come with being alive every day.

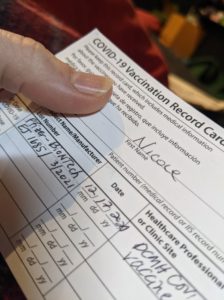

Injection site report: I have a small bruise on my left arm that I am going to attribute to the vaccine because it looks like it’s a few days old (I did not take a picture of this because it is really just a faintly greenish spot about a centimeter across, and that sort of picture is only of interest to dermatologists and forensic scientists). It doesn’t hurt, even though I’ve poked it repeatedly just to make sure.

Still seeing reports that are consistent with Pfizer’s data (1-2 days of fatigue, injection site pain, muscle and joint aches, and fever in a notable minority of recipients – in the study these were more frequent and more severe in general after the 2nd dose) from other folks who’ve received the vaccine. I’m going back to the gym tomorrow. If my arm falls off, it will make for an exciting report, but I am now 96 hours out or more from my injection. I’ll let you know how my workout goes.

I hadn’t realized how much “can I still smell the coffee brewing?” had become a part of my daily ritual, but it is. I remember when the first anecdotal reports were coming out in March or April that noted almost a third of COVID-19 patients reported loss of taste or smell, and how my colleagues and I made it part of our unofficial criteria long before it was on the ever-expanding list.

We’ve come a long way.

Also, I could still smell my coffee this morning, and I am glad on many levels.

If I have had Guillain-Barré syndrome in the past, is it advisable to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

Sort of short answer: Limited available data suggest that it is safe and advisable for the majority of people who have a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome more than a year ago to be vaccinated against COVID-19, but you should consult with a medical professional who knows your particular history in this case.

Longer answer:

Guillain-Barré Syndrome, or GBS because that’s really long to type, is a name for a group of similar syndromes — but the one that most people generally seem to be referring to can be described to medical professionals as “an acute, monophasic paralyzing illness” and to people who don’t speak doctor as “suddenly, your immune system betrays you horribly.”

Your immune system is one of those perfectly ordinary superpowers you have. Its job is to recognize things that are “not you” — foreign antigens — and not only eliminate them, but remember them so that they can’t get so close next time. It’s really good at this, most of the time.

Anyone who tells you that we have a full and complete understanding of the immune system is selling snake oil. Our bodies are almost incomprehensibly complex and the more we learn, the more questions we have. We are pretty sure that GBS results from what is called “molecular mimicry” — which is to say that your immune system, while organizing itself to fight against a foreign antigen, suddenly decides that “those myelin cells over there look a lot like this wanted poster I have in my metaphorical hands” and begins systematically destroying the protective sheath that keeps your nerve cells safe and healthy.

People who develop GBS have a range of symptoms from mild (“I seem to have become quite clumsy when I walk”) to severe (“I am on a ventilator because my body has forgotten how to breathe”). It usually gets worse over a period of four to eight weeks and then it starts to get better. At one year after onset, a little under ⅔ of patients have recovered full motor strength, and about 3 patients in 20 will have ongoing severe muscle weakness. The rest are somewhere in between.

That is some terrifying stuff. It’s even more terrifying because we don’t have a complete handle on what, exactly, triggers molecular mimicry. About ⅔ of people with GBS report a recent upper respiratory or gastrointestinal illness, and a short list of pathogens seems to be the primary drivers of this — but rare cases of GBS have been triggered by surgery, trauma, bone-marrow transplant, and immunization.

And there’s the rub. Increased risk of GBS was seen with swine flu immunizations in 1976, and with H1N1 and influenza vaccination more recently. Because this is a rare syndrome (1-2 cases per 100,000 people per year), you need really large numbers to discover increased incidences – sometimes combining multiple seasons worth of influenza vaccinations and disease to find any statistical significance.

Our best estimate at this time is that between 1 and 2 extra people develop GBS per million people given the influenza vaccine. Our best estimate at this time is that you are about 7 times more likely to develop GBS in the 90 days following an influenza-like illness (not everyone has proven influenza, because not everyone gets tested) as you would be without the illness.

If you’re still with me here:

Your risk of getting GBS from an influenza-like illness is substantially more than your risk of developing GBS from the influenza vaccine. But we can’t predict whose immune system will suddenly go rogue.

COVID-19 can probably cause GBS; it’s described as infrequent and there remains some scientific controversy, but it is a potential complication of the disease, and we don’t know which particular antigen (part of the virus particle) might make the immune system go rogue. We have not seen an increased incidence of GBS in the Pfizer and Moderna trials thus far. That should be reassuring — but I want you to review the number of times I’ve said “we don’t know” or “our best estimate” about GBS (at least 6).

Immunization recommendations in general for folks who have had GBS are based on observational data and expert opinion. That means that folks got together and talked about what they’d seen and the science as they best understood it and said “this seems to be the best course based on the information we have.” That means I don’t have a yes or no answer to give you.

Unless I am your doctor (and if I am we’re not having this conversation on Facebook, call the office!) I cannot give you the kind of personalized in-depth shared decision making conversation that has to happen about your particular case.

But I do recommend that you call your doctor and have that conversation.

I’m going to hold on to the question about long-haul COVID and vaccines for tomorrow, because there’s a lot to unpack there, and this post is long enough already.

- References for today: Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 VaccineGBS (Guillain-Barré Syndrome) and Vaccines | Vaccine Safety

Lack of association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with vaccinations

No association between COVID-19 and Guillain-Barré syndrome

How the Oxford-AstraZeneca Vaccine Works

Guillain-Barré syndrome: Pathogenesis

Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults: Clinical features and diagnosis